![]() |

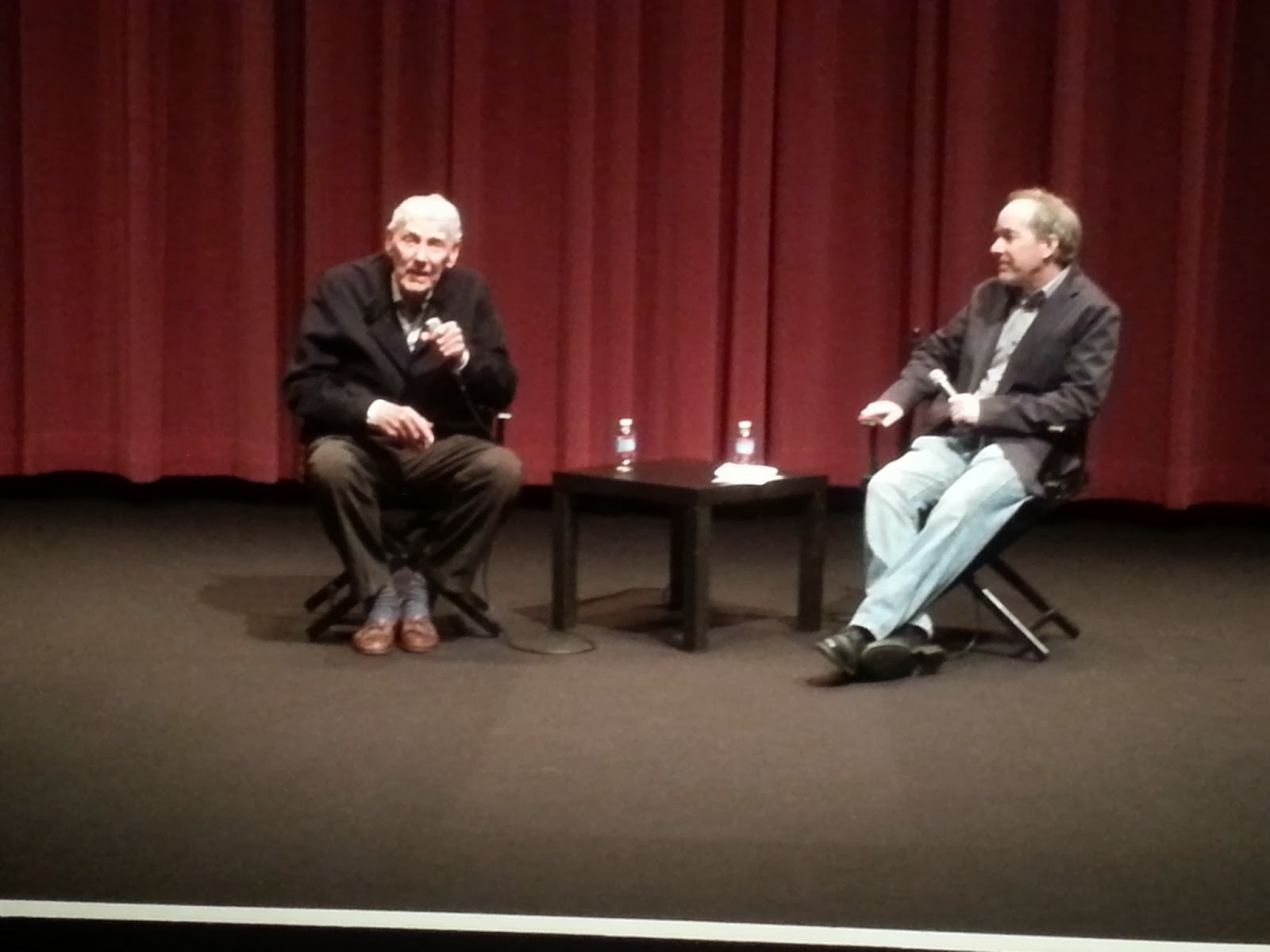

| Director Robert Butler and Archivist Mark Quigley (January 24, 2014) |

Last month I promised I would transcribe the rest of the Q&A with director Bob Butler if there was sufficient interest. There was, and today I finally finished that transcription. Enjoy!

(Recorded January 24, 2014 at the Billy Wilder Theater in Los Angeles, California)

Robert Butler: I don’t see any costumes.

(Audience laughter)

Butler: I welcome you whole-heartedly, with the confession, with the admission that I have spent a couple hours lately on the Star Trek DVDs that show the gatherings in various cities around the country. I was trying to figure out you, the Trekkies, and the legs, the popularity, the quick popularity of the show. The thought I’m left with is that I found you Trekkies a little less weird than I thought you might be.

(Audience laughter)

Butler: I drew the conclusion that between us normal civilians and weirdness and Trekkies and civility must be a measure that’s identical.

(Audience laughter)

Butler: Anyway, welcome Trekkies, whoever you may be. We’ll find you out!

(Audience laughter)

Mark Quigley: So, this pilot, NBC decided they wanted another pilot. You had already worked with Gene Roddenberry on The Lieutenant. Do you remember the reaction to this pilot? You were offered the subsequent pilot, but you turned it down.

Butler: Yeah, I turned it down simply because I’d been there. I think it was a couple years later. We were talking about that. Gene had gone ahead, I think, and produced more of a television series that he had on the air at the time and I moved on to other things. And then he came to me with the offer and I passed because I’d been there. I had heard, at the time, probably reasonably, that the network thought and said, “We like it, we believe it, we don’t understand it, do it again.”

(Audience laughter)

Butler: So Gene moonlit another script as he was making his subsequent existence, work, and the show was the result of that.

Quigley: And then this episode ended up getting cannibalized when they ran out of money later in the season with 'The Menagerie.'

Butler: Yes. I looked at 'The Menagerie' the other night and thought a lot of the manipulation was kind of clever. They had this Captain, Jeffrey Hunter, as a very distorted remnant of what he used to be, enabling an actor to sit and play him scarred and in the present at that time, answering with light signals and so on. It was kind of creepy and probably a very good idea at the time. Incidentally, fifty years ago, I saw a lot of innocence and sweetness and trust and less cynicism than we see now. Not that I endorse either one, but this is very aimed at us fifty years ago, when we were more acceptable. I mean, the special effects are a little questionable in spots, and we can see budgetary all over the screen compared to what we see today, and yet those legs, that suspension of willing disbelief that we all seem to do, happens again. We follow the damn thing. It has some beckon for us that works.

I felt that when the first shot kind of goes into the flight deck and we see the crew there, sitting there in control, and then there’s that subsequent Doctor-Pike scene that’s so good. We’ve seen that scene thirty, sixty, a thousand times – the enervated hero needs a lift, confessing to his mentor, whomever – and yet, that beckon was in there. Those legs were playing and (chuckles), in spite of the directorial superiority, the damned thing works. It’s okay!

Quigley: I had fun teasing you about this the other day, but let’s talk about your proposed title change for the series.

Butler: Yes, I thought Star Trek was heavy. I tried to get Gene to change the title to Star Track. That seemed lighter and freer.

(Audience laughter)

Butler: It’s not my business to be able to do that, and yet I was trying to convince him. I believed in it and, you know, water off a duck’s back!

(Audience laughter)

Butler: Which is okay.

Quigley: Let’s spend a few minutes going back, because you have the type of storybook beginning that people can only dream about now. This really wouldn’t be possible. You started as an usher at CBS.

Butler: Yes, I sure did. I wore a uniform for about a week with the Uni High quarterback with whom I shared some celebrity at Uni High. He and I, Ray Bindorff and I, put on the blue uniform and passed out the tickets on Hollywood and Vine to get people to come to the radio and occasional television shows. That’s pretty fascinating. Ray is here somewhere.

Then, seven years later he was on into his business career and I left TV City to take a job with my next partner, Gene Reynolds, with whom we shared an early comedy, Hennesy. We alternated for six episodes until we were both dumped and then we were out on the marketplace wailing away. Ray was there first, Gene was there second, and we’re all here now together, which is good.

(Audience applause)

Quigley: In between your being an usher and working on Hennesy, you worked your way up through what we now call the Golden Age of Television, as an associate and assistant director on Climax!and Playhouse 90. That was where you cut your teeth.

Butler: Television city at Fairfax and Beverly was the best kindergarten for learning the alphabet of storytelling that you can imagine. It was live, you went on the air every week, every other week, whatever, you saw your results that night. I watched terrific directors, associate directors, producers, writers, actors – I mean the whole operation. The cast being put together as the story told unit was just 3-D schooling. It was breathtaking and I learned a lot in those seven years. A lot of it shows, some of it’s still pretty green here, beyond the green dancer.

(Audience laughter)

Butler: But that was a great experience.

Quigley: I think you were telling me, you threw one of the first cues out of TV City onto television – the first broadcast from TV City.

Butler: Great point. TV City was being constructed and finished and was to go on the air on a given night. Shower of the Stars was to go on at seven or eight or whatever, and at that time I was a stage manager and I threw the first cue to the background projectionist who rolled the film that projected starbursts on a screen in front of which our host stood. So, I started that.

(Audience laughter and applause)

Quigley: Now, from there, after Hennesy you did The Dick Van Dyke Show [and] The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. How did you become the go-to guy for TV pilots? How did that start?

Butler: Well, after crediting Television City and all that good experience, I happened on a pilot where the director had gotten gun shy or something and needed to be replaced on a given afternoon. They weren’t shooting yet, they were in preparation, and my agent said, “I’m going to get you a show.” He got me into that producer, and we talked, and I got the job of Hogan’s Heroes. A half-hour, one camera comedy, in black and white, and black and white helped the Nazi comedy, if that isn’t an oxymoron.

(Audience laughter)

Butler: But, it was a terrific experience and that was early in my working life. I don’t remember what the second pilot was, but with that start, and that good, hit reaction that that show made, I’m sure that’s in the mix there, somehow an issue.

Quigley: And then, shortly after that, would have come Batman.

Butler: Yeah…

(Audience laughter)

Butler: I say that out of admiration for preposterousness because that’s totally what that was. Lorenzo Semple was a good family friend – a terrific writer, a well-known craze-o, intellectual, creative guy – whether Lorenzo turned that crank or the reputation about pilotry [sic] was at work, I don’t really know. I remember thinking that the material had to be treated very genuinely because it was so crazy. I mean, Batman explains the villain to the police commissioner, the Riddler, “He contrives his plots like artichokes. You have to strip off spiny leaves to reach the heart.”

(Audience laughter)

Butler: Well, that isn’t a joke, exactly, but it sure ain’t reality, either. So I was aware it had to be carefully handled and I did, with good support from the studio boss at that time, Bill Dozier, who was very wise to have hired Lorenzo in the first place. I mean, that’s crazy writing, and really good, and your friendly director got it, and understood it, and delivered it in an appropriate style for it.

Quigley: You came up with the motifs of having the canted angles for the villains and some other things that just stayed with the series – became hallmarks of the series?

Butler: I just felt we couldn’t not, because when you opened a Batman comic book, which I certainly did as a younger kid, why, the pows, and the zowies, and the biffs and bapps were highlights of the action sequences in the comic strip. Well, how do you do that in Technicolor without biff, boom, bang? You know, [we] just had to. It sounds like an innovation, and honest to God it’s just something that we were conditioned to do. We couldn’t not, so that’s directorial genius again.

(Audience laughter)

Quigley: Now, you and I have talked about this, but Batman was a cultural phenomenon at the time, but for you it was just – you moved on relatively quickly. You did, I think, three sets of two, and one of your villains was George Sanders?

Butler: Yes, yes.

Quigley: But you didn’t get caught up in the cultural phenomenon that was Batman at the time?

Butler: No. I’m paid not to. You know, I’m paid to get that story told and delivered and the disbelief suspended as effectively as I possibly can, and that’s what I do and always did concentrate on, maybe to a fault, but that was my interest: the story, the behavior of the characters, the assistance to the actors in doing what they were trying to do, and the delivery of all that to the audience. There aren’t any tens, there’s no pure vacuum, and the actor is never quite right, the scene is never quite right, [and] the finish has not been applied until take two plus all the post-production and the appreciation. Then it gets…closer to good or excellent or perfect. Perfect is just way below what I’m talking about, somewhere else.

![]() |

| Director Robert Butler and Archivist Mark Quigley (January 24, 2014) |

Quigley: Decades after Batman, you’re called to launch another comic book series with The Adventures of Lois & Clark.

Butler: Yeah, Lois & Clark was much the same thing. The writing wasn’t as crazy…it wasn’t less established, certainly. Superman was certainly as established as Batman, and yet there was more sadness in Superman, because here was this person from somewhere else, who was trying his best to fit in and being too, too, too exceptional, etc. That rode with that character a lot, and it was in the writing and in the concept, maybe. I don’t remember the comic strip that well. I have a feeling it probably wasn’t included in the comic strip. It probably was increased for the living rooms and the understanding of a superhero. We were always pleased with the thought that Batman was a human being, who had resources and Superman was this invincible…beyond person. One was for sure going to win; the other, Batman, had to engineer and persevere his winnings. But, on the other hand, Superman had the sadness. He was a freak, he was a foreigner. It cracks me up to think of the guy, you know, and that was played, granted, not a lot, but that’s in there. That brought legs. The audience is being carried in the suspension of disbelief being pursued and realized.

Quigley: In the history of TV, statistically, I mean I haven’t done the analysis, but I really don’t think there’s any other director that directed as many different series as you did. Part of that was by design. You didn’t like to stay in one place too long, but if you look at the scope and scale, you went from Batman to Ironside to Kung Fu to Hawaii 5-0, just to rattle them all of. What was it that propelled you to all these different [shows]? You were welcome wherever you went, you could do any show you wanted, and you did as many, it seems, as you could.

Butler: Well, the freelancing I adored. Doing different things, not knowing what two months was going to bring, and where the pay window was. I loved the freedom and the disconnection of all of that. I mean, it took me a year and a half to get used to it because, you know, I was a middle class kid raised on order and process and repetition and all the rest of it. As a young kid musician I may have gotten into that less known pattern, and maybe that’s why, and I really adored that and was confident that it would turn up in three weeks or three months. It was luck. One can’t dismiss the marketeering and concentrate on the issue. You’ve got to do both and for some reason I did much more of the storytelling preoccupation than the marketeering of myself and the results were good enough so that positive results followed me, or something.

Quigley: I think one of the other most remarkable things about your career is that decades after you started you had reinvented the medium with Batman in the sixties and with Star Trekand then this kind of all culminates in Hill Street Blues, which, again, is something that redefined television, and redefined television in the eighties. Let’s talk about Hill Street Blues and let’s talk about that whole philosophy of “making it dirty.”

Butler: It was a great collision of a number of elements. Timing, of course, had a lot to do with everything. I was at a point where I could act on some of my hatreds, namely, cleanliness. I hated cleanliness. Star Trek was so cleanly [sic]. I tried to get the scenery butchered up as though it had been in use, and I couldn’t do it. The production designer was already working, and I lost that argument. It’s largely as many arguments as you can win. The more arguments you win, the more singularity the yarn has. It’s not rocket surgery, it’s singularity, recognition of people at work and at play consistently and clearly and understandably. That’s what we’re trying to do, so we win as many arguments as we can.

I took Remington Steele to Grant Tinker, who was a friend of mine on The Dick Van Dyke Show. We’d known each other a long time. And he said, before I give you an answer on Remington Steele, let me give you a script, and he sent Hill Street Blues to me. And, immediately, the directorial disdain surfaced.

(Audience laughter)

![]() |

| Director Robert Butler and Archivist Mark Quigley (January 24, 2014) |

Butler: Do we really need another cop show? So that kind of cleared my head and I knew I had to go to work again. And, I had the boss’s ear. Grant Tinker was the boss. I had the certainty, which was that cleanliness was hideous and messiness was appropriate, and more real and more recognizable also, so I was able to shake that execution of that story up, overlap the dialogue, [and] make the lighting look kind of routine and hideous and improper in places. Truly, the cinematographer, a very knowledgeable Hollywood guy, knew when I said, “Look, let’s make this thing look awful. I want it to look awful.” He knew I was talking about Hollywood awful.

I mean, we were going to be able to see everybody, it was going to work fine, but it just was going to be less shiny, glossy, perfect, surface-y, clean. So he would come up to me, I think just to assure himself, and he would say, “Listen, man, it’s looking pretty bad.”

(Audience laughter)

Butler: And I would always say, “Good. Make it look worse.”

(Audience laughter)

Butler: And that’s really the truth of the way we worked. You know, the show had legs. Let’s face it, it had legs. I remember the fourth act in the hour form having not much action. There’s a tie-down situation around a liquor store where there’s some hostages inside. That’s not a very big opportunity for a chase with people tied down and movies finish with some form of action, chase, gunfight, whatever, and I remember mentioning to the guys, “Guys, we’ve got a talky fourth act.” I mean, sure, the EATers, Emergency Action Team that Howard Hunter, Jim Sikking, he’s here tonight with us, were active and they blew up the back door and then shot up the liquor bottles, etc., but it was clever and it was wordy and it was somewhat action-less. I expressed this as humbly, secretly, arrogantly, as I possibly could, and blank faces. You try to win an argument three times and if you don’t you forget it and move on because the clock is ticking, the sun’s going down, the teacher is going to take the kids away from you, and you have to get the damned thing shot. So, I gave in, and your friendly director was wrong, man, because the fourth act played great. So bet on me less than a hundred percent of the time.

Quigley: Well, they invited you back to direct more than just the pilot of Hill Street, so you did something right. We have time to take some questions and then we want to come back to introduce Columbo, but let’s first take some questions.

Audience Member #1: Hi, you said you went to Uni High here in West Los Angeles. What were your goals as a high school student, and how did you get into directing? You started as an usher, but what was your experience in directing, and did you learn directing in college like they do these days? What were your goals when you were in Uni High?

Butler: My answer, the director’s answer, is get as close to the scene as you possibly can. The making of the scene – the actors, the directors, what’s happening there. That’s where the action is. That’s where the storytelling takes place. You combine the page with the actor with the cinematography and all of it, and you deliver that to the audience. I knew in high school with my dance bands, because I led them easily and got good results in the rehearsals and so on, that I was some kind of idea man, but I didn’t know what, so I sent letters out to studios and got no results and went to work at CBS as an usher and, more importantly, got into production, got near the storytelling. Not at it yet, but near it. Usher, receptionist, production clerk – a couple, three years of production clerk. What lenses are to be ordered, what cable pullers are to be ordered, how many extra cameras, production, how you do it, the tools that make it work – production assistant. Then stage manager, handling the cast, being there during rehearsals, and watching the director and the actors put the show together and make it recognizable and kind of real and believable. I stood right next to the directors as that was happening as a stage manager. Then, co-pilot, associate director. I did it with directors and now I’m in the booth, in the control room, with the pilot, and I’m like the co-pilot, readying the shots and taking care of the crew, all well-rehearsed under the director’s captaincy, of course, but then co-piloting and then getting a break on Hennesy. Those are the steps.

Sidebar – I’m sitting at NBC playing trombone with the teenagers on a radio show. That’s radio show.

(Audience laughter)

Butler: I’m watching this guy called a contact producer – he’s the director – Ed Cashman, apparently a very well-liked, effective guy. Brooks Brothers suits, kind of jazzy, I knew it wasn’t totally sincere, his act. I realized there was a lot of frosting going on there, but I was watching this guy. He fascinated me, and the idea dawned on me, and this is partly in answer to your question, he’s having fun while he’s working for a living. Ding!

(Audience laughter)

Butler: That was new to me at age sixteen or seventeen, and I carried that with me, and have told our kids, “Don’t work for a living. Find another way.” That’s in the mix, but that’s a capsule of moi.

(Audience applause)

Audience Member #2: As you look over your respected career being the director of so many pilots, I wanted to ask, as you look as the pilots transitioned to series, did you agree or disagree within any casting changes between the pilot and the series, and on those few pilots like Sirens, The Brotherhood, and Our Family Honor that were not a success that Star Trek and Batman and Hogan’s Heroes were, did you understand, perhaps, why those pilots or series did not follow the success of your initial presentation?

Butler: The second part of the question very much has to do with legs. Does it work? Is it believable? Do the audiences recognize the people? Do they sympathize with them? Do they pull for them? Does the notion have legs? Does it carry its audience? Certain ideas just do and certain do less so. Cop shows, wearying as they may be, have legs. The doctor shows used to have, more than currently in our lives, legs. And that’s very mysterious. Only you really know what legs are. We’re trying to figure them out and label them, but you know, and we, as we sit with you in test nights, we can – it’s amazing the way you speak to us as we’re watching a piece of work – where you’re quiet, where you’re fidgety, where you chuckle, where you laugh, whether you’re quiet as a cemetery. All that is clear beyond our knowledge – you know what legs are and we’re always trying to figure out legs and retrospectively, I can see largely, that some of the shows, have better legs than the other[s].

The first part of the question I think has to do with casting and execution further down the line. That’s very personal. That has to do with winning arguments, as I say. You’ve got the character on the page, and the actor walks in, and in eighty percent of the cases you can tell within the first six footsteps across the room whether that actor is going to be in the neighborhood for this part or not be. It’s very clear and it’s very personal. You have to win the argument with the others in the room, the producer and the network, whomever. That’s kind of wordy. What it has to do with is, as you’re telling that initial story, you try to make it as clear as you possibly can with the use of the casting trickery, whatever that may be. Later, as you watch the show, you don’t care, man, you’re on to other things. You’re interested in the next job, not the last one, the next one, or something.

Audience Member #3: What was your technique with the actors, and did it change if it was a pilot, or did it change according to the actor?

Butler: Yes, it did change with almost each actor, slightly. What you’re trying to do is get the actor to be his or her best. I don’t necessarily mean shriekiest [sic] or loudest or more teary or with bigger whimpers. There’s something else inside that’s organic that they are expressing, the character they have read on the page, with who they are. Relaxation, like in sports, is the best way to get there. I ‘m told that in baseball, when you hit the home run, there’s not a crash or a bang or a crunch, there’s a click. All the energy is channeled and it’s efficient and the thing goes over the fence. If you’ve got the actors confidence to the extent that he/she can relax and believe what you’re saying, or question what you’re saying, and go 180 to argue with you. If they’re comfortable enough so that they can get conversant and comfortable with what they’re trying to do, and you chose them or didn’t in those first seven steps across the office, then you’re doing a good job with them. As it changed through the years…

[At this point, my phone reached its recording limit, resulting in about 30 seconds of missing audio.]

Butler: You’ve realized that they’ve done semblances of what they’re going to do with you thirty, fifty, a hundred and fifty times. They know how to do that. Now, the thing’s that different, is that the words are different and their partner is different. So you’re getting a new combination of a recognizably comfortable character like Tilly who lives down the street or George on the next street over. You recognize those people and you don’t want to get beyond, too far, you want to be a little beyond the recognition, which is another point I grant, but you want to be a little beyond the recognition so it’s fresh and unusual and slightly startling. Slightly– not usually startling because you don’t know what the hell you’re looking at, except it’s an odd combination of the discreet sell-out (chuckles). The intelligent sell-out with the audience being considered at every turn, every single constant turn, only the audiences know for sure.

![]() |

| Director Robert Butler and Archivist Mark Quigley (January 24, 2014) |

Quigley: That’s a perfect segue to talk about one of the most distinctive shows, if not the most distinctive television series of the seventies, which is Columbo. [It] basically broke a lot of rules, and there was a lot of reasons why it worked and a lot of it had to do with the directors that were working on it and the star as well.

Butler: Yeah, I was going pretty well, so it wasn’t unreasonable of me to be offered a Columbo or two and the producer was a terribly good guy and a funny guy and so on. Peter, as a trained accountant, with his accountant and lawyer, had determined before I got on the scene in the third or fourth season that everybody was making a zillion dollars and he didn’t have to grind them out so bad. They were all scheduled at nine days, and they all went ten, eleven, twelve, and nobody was saying anything. You go over a day or two and boy, they’re on your back, they’re above you like flies, and I kept looking around and there was nobody there. I had a good time, but it was odd and questionable, and really fun. The content was fun, Peter was fun, very respectful, interested guy, who said, “Great, let’s move on. Oh, oh, oh, no, man, let’s just, let’s just, do we have time for one…” [Peter was] always sane, reasonable, encouraging, [and] respectful. “Do we have time for one more shoot?” What am I going to say? No?

(Audience laughter)

Butler: “Yeah man, sure, let’s do it! Go, guys, let’s go.” That’s where the time goes – Peter perfecting and refining. Again, there’s no perfect, it’s refining what he’s doing for that audience. And I said, to Roland Kibbee, the producer, because of the conditions I’ve outlined to you, [it] was strange, I said, “You know, this is really a good show. I’d love to direct one sometime.” And he said, “Yeah, I’ve got a lot of writers not writing ‘em, too.”

(Audience laughter)

Quigley: Really quickly, your take on the Columbo character that you can enlightened Peter Falk a little bit, in a way, is pretty interesting.

Butler: Yeah, Peter hadn’t thought of an idea that was obvious to me, and I hung my interpretation on, and that was that Columbo wanted everybody he dealt with not to be guilty. He wanted them to be innocent (chuckles). I mean, you know the scene. “Listen, Mr. Stone, I’m so sorry that I had bad thoughts about you. I promise that I won’t do that again, sir. Really, good luck in your life, and all your thievery, and all the rest of it.”

(Audience laughter)

Butler: “I just want to say it’s been an honor being with you, sir.” And he walks to the door, and he stops, and he turns around and says, “There’s just one thing…”

(Audience laughter)

Butler: And you know that in the next three minutes the villain is going to get it in the neck. That’s the way the show was built. In answer to Mark’s question, it was an absolutely magnificent marriage of the man on the page and the actor. Whether all that fiddideling [sic] that Peter did was in the original material, or whether it was just suggested, I don’t know, but his training, his orientation, his positivism, I guess, with that character was just strong as an ox. As we will see, he is irresistible. The people around him are good, the performances are good, good people are hired, Jim Sikking is in one of the scenes… It’s just a very, very well-mounted, well-organized, supremely performed show. Now, we can get snobby and say it gets a little cute at times, and what he does is a little redundant, but try and resist it. Try and resist it! You can’t, man. The guy knows the character, he knows the show, and he knows how to reach us, and he did time after time after time.

Watch for one scene. Mariette Hartley, a very nice actress, plays an editor in the show [‘Publish or Perish,’ a season three episode of Columbo], and she and he have a scene that’s just very quiet and natural. It’s not unlike the Doc and our Star Trek hero, Jeff Hunter, that early scene that I’ve said we’ve all seen many times before. There’s a solidity and a familiarity and an ease by them and by us because we know what they’re dealing with and what they’re doing is so terrific and solid. You’ll notice that scene with Mariette and Peter in Columbo.

.png)